I’m sorry, I tried, I love you

by G.G. Silverman

Issue 8: Weird | 1,415 words

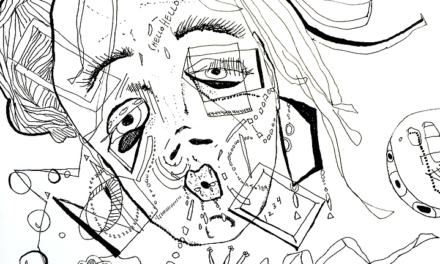

© k_yu/Adobe Stock

Lately, you are forced into a gender role that you do not want: the woman who cleans her house every morning. But it’s not just any kind of cleaning, not in the pedestrian sense. It’s the kind where, every day, you wake at 4 a.m., before the rest of your family, and you put on a hazmat suit, goggles, and a respirator, and you clean your house in the dark.

Well, not totally dark; there is the flashlight you use to check every single surface for the shards. They are fine, a sliver of a millimeter, sharp threads of glass. They can only be seen by flashlight, held at an angle, just so. When they glint, you can see them: an intricate, haphazard web that’s beautiful and dangerous. You wipe them away slowly with a damp cloth, careful not to send more surging into the air. You live in a 3,500-square-foot home, because it’s what your social circle demanded. Cleaning it takes a while. Hours, actually. And you do this, painstakingly, every morning.

Meanwhile, the children and your husband sleep soundly in their bedrooms, where, miraculously, shards have never materialized. No one really knows why the shards happen, though there is a pervading popular superstition, one bordering on law. We only know that they itch and burn when they come into contact with the flesh, the eyes, and the lungs. When they’re awake, your children have no sympathy that you’ve scoured the house for hours, until you’re ready to collapse from exhaustion, even though it’s only 6 a.m.

At the kitchen table, Tanner, four, says with perfect diction: Mother, clearly you have angered the House Gods by not making an offering. You can only blame yourself.

Liddy, seven, nods in agreement over a plate of waffles you’ve freshly made; she cites how you neglected to leave apples or fresh meat by the hollow at the base of the tree that looms over the far edge of your property. All the other mothers remember, she says.

Daniel, your husband, is too preoccupied with work to say he agrees. He grabs his shoulder bag laden with gear, steals a waffle, and disappears into the garage to leave for work.

Soon, you will drop Tanner off at Advanced Daycare for the Precocious and Liddy off at the Performing Arts High School for Talented Elementary-Aged Children, and you will return to your home to clean for several more hours, wiping shards as they fall, then leave yet again to pick up the children, who will remain unsympathetic. They will not ask you about your day. Instead, they will talk about the social mores of school—how hard it is to not have an internet-enabled lunch box, or the uncoolness of last week’s holographic shoes. You can’t tell them how you ran the air scrubbers on Extreme Clean Blast mode for hours while you went grocery shopping at the Organic Palace, where most women kept their distance from you, because you wore the telltale sign of someone afflicted by The Shards—hard red lines pressed in your forehead, over the bridge of your nose and around your eyes, marks left by the safety goggles. Your cheeks are marred by rings around your mouth, etched in your skin by the respirator. To have received shards is the ultimate mark of shame—there is no service that will come and clean them for you. Clearly, everyone at the grocer’s must think when they see you, you have displeased the House Gods. In our suburban utopia, there are unspoken rules inflicted on women: it’s your job, ladies, to leave an offering. On any given day, there may be one or two women at the store who wear the signs of failure. Today, you were alone.

At Parent-Teacher Association the next day, no one asks how you are. That question is reserved for the parents who appear to be successful, winning at life. The marks on your face say otherwise, and you know what they’re thinking: You were supposed to leave an offering.

Later that night, at home again, everyone is silent at dinner. No one appreciates how you’ve cleaned the afflicted part of the house until it’s safe to sit in and eat, thanks to your efforts to contain the shards that would otherwise prick their skin. No one acknowledges it because, well, you have brought this upon yourself. Overnight, when everyone’s asleep in rooms that are safe, more shards will tumble from the air, and they will fall on your kitchen table, the chairs, the dining room table, the counters, the art desk in the playroom. And the next morning, you will get up to clean again, noting glumly that you’ve been cleaning for weeks now, and you will feel a little despair.

At 3 a.m., when the veil between worlds is thinnest, you slip out of bed. Your husband’s side is empty and cold; he has left for a business trip. You creep through your home, careful to avoid disturbing shards that have settled thus far. You exit, walking to the far edge of your property, feeling the wet grass through the fabric of your slippers. The neighborhood is dark and silent as you approach the cedar that soars from the farthest edge of your yard, the one with the hollow at the base. It’s then that you see them in shadow, a giant rabbit and a giant crow, yin and yang, prey and predator. They flank each side of the tree, with eyes glowing red. You know in your heart that these are the House Gods. You’d never seen them before; you thought they were a lie to keep women in line. Nightmarish and beautiful in their blackness, they tower, unblinking and unsympathetic. You’ve heard that the shards they’ve gifted could be just the beginning—if unappeased, it’s been said that there’ll be no end to the suffering that befalls you.

You only approach the House Gods so closely, preferring to observe from a distance. They are soundless, and you are without speech too, and you behold each other, you and these terrible beings. There is a mild breeze; it ruffles the fur of the rabbit and the fine feathers at the base of the crow’s neck ever so slightly.

From the soil all around you, thin black tendrils poke from the earth, slick and sudden. They thread over your feet, climbing your legs. Panic stabs your heart.

“I’m not afraid of you!” you shout, unable to control yourself.

The rabbit and the crow remain unblinking, still terrible in their silence.

You regret what you’ve done, and tear yourself away, looking back as you run. They still loom, large and darker than coal. And you still haven’t made an offering.

Inside your home, the digital clock on the microcooker tells you it’s 4 a.m., when you’d normally pull on your hazmat suit and start your cleaning ritual anew.

Instead, you approach the bedrooms, gathering up one sleeping child at a time to carry them out to the car. They have always been heavy sleepers, and for that you are thankful. As you buckle them into car seats you admire their sweet upturned noses, fine eyelashes, cherubic lips. For a second, you think about having more children, then you think, no, no.

Once bundled in the car, you drive them to your mother-in-law’s, all of you still in your PJs. You leave the car parked in her driveway, with a note pinned to Tanner’s and Liddy’s chest. It says: I’m sorry. I tried. I love you.

As twilight breaks, you roam your mother-in-law’s neighborhood, stealing a child’s bicycle. You ride toward home, wet slippers making pedaling difficult. You note the sprawling houses, monsters in their own right, hulking and hungry. Back at your own, you step off the bike, leaving it at the end of your eighty-foot driveway. From various spots in the lawn, more black tendrils birth, seeking, searching. You bound inside, climbing stairs, running all the taps in bathtubs and sinks at full force. You crank the gas on the stove, each knob open as far as it’ll go. Pungent fumes thicken the air. Somehow, someway, this home will meet its end.

No one can ever return.

Outside, you hop on your stolen bicycle, heading nowhere, anywhere, as tendrils birth in the shadows. You have unseen forces to outrun, ones that are mysterious and beyond your control. You refuse to make an offering. You refuse to make an offering.

G.G. Silverman

G.G. Silverman’s short fiction was most recently nominated for the Best Small Fictions anthology, among other honors, and her work has appeared in NOT ALL MONSTERS (a Women of Horror anthology by StrangeHouse Books), Psychopomp Magazine, Corvid Queen, Fantasia Divinity, Pop Seagull, The Molotov Cocktail, and more. She is currently at work on a short story collection as well as a poetry collection. When not writing, she teaches others how to do it at Edmonds College. To learn more, please visit www.ggsilverman.com.