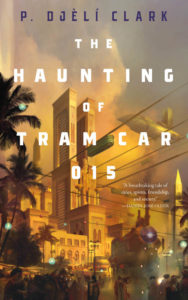

Review: The Haunting of Tram Car 015

by Yomna Osman and Jermuk Dalmas

Issue 9: Alternate History | 1,248 words

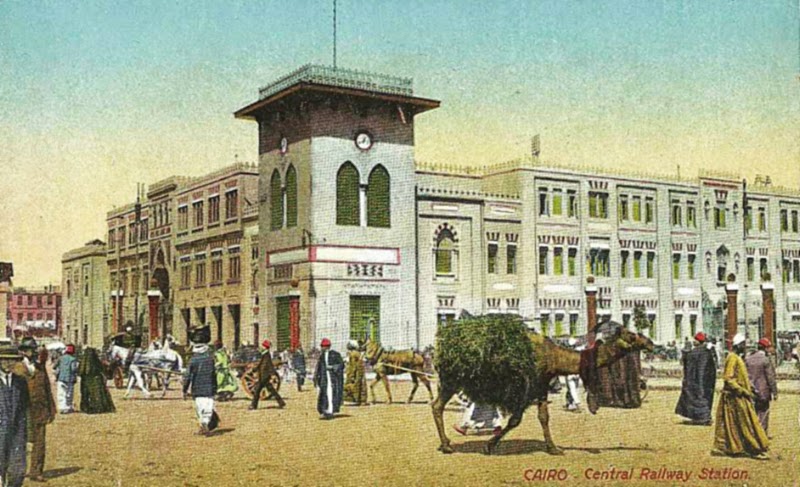

Cairo. Central Railway Station. Unsigned

Editor’s Note: This review contains spoilers.

The Haunting of Tram Car 015, a 2019 novella by American writer P. Djèlí Clark, became a finalist for three awards this year: the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus. The novella takes place in 1912 Cairo, Egypt. In this version of history, Cairo has institutionalized and bureaucratized magic. Two agents are called into an office in Ramses Station, Cairo’s main train station, to solve a case concerning a mysterious haunting of a tram car. They meet many intriguing characters on their journey, including an Armenian with a sweet tooth.

Curator Yomna Osman and podcast producer/musician Jermuk Dalmas discuss the novella over tea.

Yomna Osman: So, what did you think about the book? Let’s start with some impressions.

Jermuk Dalmas: I enjoyed it. I like novellas with good stories and strong characters, and this was that. I had fun discovering the world.

YO: I read some of the published reviews for this book before our conversation. A lot of writers described The Haunting of Tram Car 015 as delightful; I think it’s exactly that— delightful. I found the world Clark created to be well designed and thoughtful. I most of all enjoyed all the characters who were very generously created and portrayed. I also loved the parts discussing and describing the city, especially Ramses Station.

As you know, I am Egyptian. I lived and grew up in Cairo. You are half Armenian. You grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. I am very interested to hear your take on the characters, the very present Armenian elements in the story line, and the Cairo stuff.

JD: When I was reading it, questions going through my head were “How much of this was genuinely like 1912 Cairo?” and “How much of these descriptions are real?” Because of that, I wasn’t quite sure how to take the Cairo stuff. But I liked the descriptions of the city. The text made me want to know more about 1912 Cairo.

YO: Well, the first thing that I noticed were Arabic terms generously peppered in Clark’s English text. Usually, that can easily put me off, especially when the writer isn’t bilingual. When that happens, I feel like the text is written to try and include me, a bilingual Egyptian, but only in its performativity. So, I was a little weary. But, I think ultimately, Clark actually worked with the second language very well. By the first few pages, I stopped noticing the Arabic words. I started to feel the world he created. That might have something to do with the alternate history element. I wasn’t looking for my Cairo anymore. How did you read it as a non-Arabic speaker?

JD: I just felt like this how the characters would be talking. Whenever I read a word in a language I don’t know, I assume that it will either become clear in context or that it’s okay that I don’t fully understand it. Clark is not Egyptian or an Arabic speaker. He is American Caribbean. I was kind of curious how he ended up writing about Cairo in 1912 and, also, how he ended up bringing in Armenians.

YO: As a curator, I think about who gets to tell stories a lot. I certainly thought about that when picking up the book.

JD: It was interesting to read the Armenian part.

YO: Do tell.

JD: I didn’t know that there would be references to Armenian culture in the novella. So, that was surprising. In the first page or two, the characters are eating this sweet that I really like and that I would always eat when I lived in Armenia. It was fun to have them eating it. Sujuk.

Armenians come up again throughout the story, and I have a lot of thoughts about it. First off, historically, because this is an alternative history, it seems like Armenia is its own country, which it wasn’t in 1912. Armenia wasn’t its own country for 1,000 years, then it became its own country in the 1990s. Also, right after this book takes place is when the Armenian Genocide happens. It doesn’t seem like it is going to happen in this history.

YO: Why do you say that?

JD: Because Armenia is an independent country in the book. The genocide happened because Armenia was a part of the Ottoman Empire. A high percentage of Armenian stories are about the genocide, which started in 1915. It is nice to have an Armenian story that doesn’t just focus on that. It is also interesting when non-Armenians feature Armenians because that doesn’t happen very often. Usually when it does, Armenians are pretty exoticized. They are this intriguing other in the few times they have come up. That seems to be happening here also. The story is set in Cairo, but there is this mysterious thing that comes from Armenia called the Alc, which is a real thing in Armenian culture. I wasn’t too bothered by it because I was mostly excited to have Armenians featured at all.

YO: There is a large Armenian diaspora in Egypt. Having an Armenian story line for me read realistic. I am really happy that you brought up Sujuk because when I first read it I thought it was Sojouk, which is a spicy meat sausage.

JD: It is also that in Armenia, there are two different things.

YO: It was confusing for me to read that people were eating it right out of their pockets till I understood that it was a sweet. My grandparents never mentioned it to me as a sweet.

I am intrigued by this version of history that Clark created. He was able to create a powerful image of a successful decolonization of the South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) region. For me, a successful decolonization is one in which the cultures intermingle, as described in this novella. There are less borders, less demarcation. There is a lot of space for difference to exist and to be held, which I think speaks back to your point about the othering not being bothersome. The story didn’t portray Egypt in a nationalistic light, as a land that holds difference—a narrative that I grew up hearing and very much dislike. I really appreciated this imagination of a successful post-colonial region.

JD: Every culture had its own spirits that were separate from one another, and they all had to learn about each other to understand them.

YO: The creation of a space where all learned was very powerful.

JD: How does Egypt fit into the world stage in this book compared to what was actually happening in 1912?

YO: The clearest thing to say here is the invisibility of colonialism in the novella. In 1912, Egypt was still a British colony. A lot of the political and social activism that would be happening was anti-colonial. The novella didn’t invite the British. There was almost no recognition of a western gaze. Rather, the story gave a multifaceted shot of the region.

JD: And they give a reason for that in the book.

YO: The Magic. That leads to a lot of space for imagining a non-western sense of history and region building. I must say though, the bureaucracy in this magic ministry was spot on. It was as nonsensical and frustrating as I know Egyptian bureaucracy to be.

JD: I liked this novella a lot. I am really excited to see what else Clark does.

YO: And I am excited for you to visit Cairo.

Yomna Osman

Yomna is a curator and writer from Cairo, Egypt. She recently joined Speculative City as a contributing editor.

Jermuk Dalmas

Dalmas is a graduate from Starfleet Academy and writes music, words for music, words for podcast, and also reads a lot of science fiction.