A Tool to Carry Us

by Stefani Cox

Issue 2: Game | 1,882 words

©njavaka

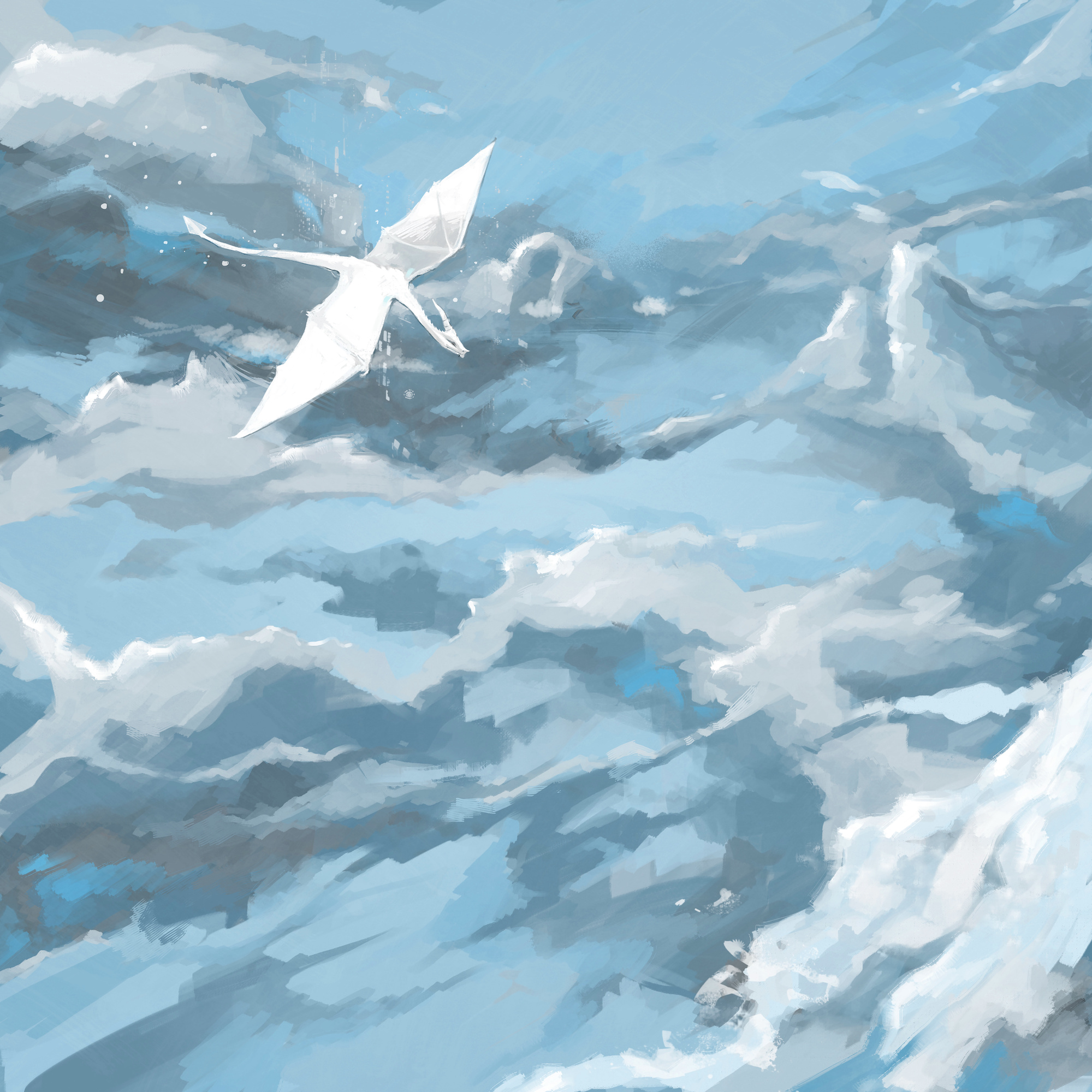

Teal is feeling frisky today. She dips and soars through thick haze above my head, cutting the miasma like a wind sail. The neon blue-green belly she’s named for flashes in sharp contrast to her jet-black scales. It’s a patterning I know well, engineered specifically to soak up maximum sunlight every time she climbs above the grey atmosphere.

Each time I’m up here, I try to spot the local landmarks as a way to eyeball the daily fluctuations in air pollution, which generally clocks in somewhere between bad and worse. Today, I can just make out the spire on city hall about a half-mile away, so that’s a good sign. Visibility is better than it has been for the past week.

A miracle baby, Teal was the first dragon our company created that actually flourished and grew into the full-powered beauty she is today. She started out small enough to fit inside a backpack, and now, decades later, her wingspan covers nearly half a football field. I still feel a jolt of pride watching her in action as she hurtles through dirty air toward the target. Three. Two. One. Bingo.

Teal blows for all she’s worth into a red-rimmed pipe on the rooftop, fifty yards from the one I’m standing on. It immediately erupts into flames. Excellent. A load of energy like that should be enough to power this quadrant of the city for a full week, even with the number of households skirting the summer electricity caps.

You’re welcome citizens, you’re welcome.

Most of them won’t spend more than a couple minutes a year thinking about the work we’ve done to bring them lights and air conditioning—perhaps only when it comes time to vote on taxes to fund our work.

The spectacle of watching Teal is just as riveting as ever, but this morning I find my breath catching in my throat. I am planning to put in my resignation next week, which means this is my last official visit, a goodbye of sorts.

Pushing seventy, I know it’s time. Still, I can’t help but wonder what waits for me on the other side of my career. Cultivating dragons is what I’ve done for more than forty years. It’s who I am.

I’m not sure I know who else to be.

••••

Wind power and solar power—while brilliant inventions of a prior century—could only ever get us so far. The ultimate problem was that that the farms took up space. That little detail was fine when the world was seven or so billion people, but at nearly twice that, the math had to change. Plus, the smog had begun to thicken.

First, we tried designing more efficient turbines and panels to absorb the dwindling sunrays. There were great engineers working on these projects, and they made real advances. But it was clear that in a matter of time, the exponential population growth—along with the related housing sprawl—was going to leave their efforts in the literal shadows.

I was one of those engineers, a later wave of them anyway, with more of a bio bent. Our team wanted to find an organism that could substitute for or amplify the technology. My claim to fame is that I was the first one to look up.

Well, that alone wouldn’t have meant anything if I hadn’t also spoken up, as black women are still somehow less visible around the engineering drawing board. (Though I like to think I’ve had at least a little impact in that arena over the years.)

Some people wonder what I thought about when I looked up at our rapidly greying skies all those years ago. Something quite simple, actually. I figured, what an awful lot of space up there.

••••

After Teal deposits her fiery power, she strikes a sharp angle upward and beats her massive wings as though gravity is a mere annoyance she needn’t put up with. I don’t blame her for wanting to return to the sunny layer above the particulate smog that humans have unleashed closer to the ground. It’s where all the dragons hang out, save for when they deposit or come in for a taste of the fertilizer-like gruel we’ve designed for their optimum efficiency and health.

In a sense, their habits are perfect because what we want them to do, what we created them for, is to collect the energy from a sun we can no longer reach ourselves. When they bring it down to us, we redistribute it to power our buildings (which are as green and efficient as we can make them) and provide artificial light to the few plant species we’ve been able to keep alive. The plants feed the livestock, and so on and so forth up the food chain.

Even knowing that our beasts belong to the sky, after all this time, a part of me does yearn for a hint of sentimentality. I imagine a slight wistfulness into the arc of Teal’s upward sweep. I wonder if she’ll miss our weekly check-ins after I’m gone.

Are dragons a forever solution? Of course not. I’ve made my contribution, and us old hats are stepping down to give the next generation a shot at self-preservation. I’m fine with that. When has our society ever functioned otherwise?

••••

Engineering the dragons wasn’t the hard part. That was just a matter of splicing different DNA strands together and handing the plans over to the incubator folks. Add a couple years of nagging meetings and boom—just what we were looking for.

Teaching the stubborn beasts to do what we wanted was the real trick. Which is how I ended up moving from my position as their head bioengineer in my forties to more of a “trainer,” we shall say. Though, with dragons, the best you can ever really do is persuade.

Some intern actually worth her salt (I told you I tried to institute some changes around here) was the one to suggest we make the energy collection process into a diversion. Maybe she was just tired of having to show up each Monday in a new set of clothes, the last having been singed by grumpy dragon breath. Whatever the impetus, after beating down the umpteenth small fire on my own shirtsleeve, I thought it was the best idea I’d ever heard.

The game we came up with had to be something they actually liked, something our winged protégés wouldn’t get bored of too quickly. In the end, the complexity of the game didn’t matter as much as the thrill of it.

It’s simple really. The dragons fly around to their heart’s content in the upper parts of the atmosphere whilst their specially-designed skins collect the product of our ever-heating sun. Their bodies metabolize the light into energy—fire energy to be exact. Some of the sunlight sustains them through a complicated photosynthesis process we’ve never quite figured out. (Don’t believe scientists who tell you they understand everything about the beings they create. The gruel we dole out functions as a sort of vitamin on top of their less-tangible fare.)

Once they’ve collected enough energy, the dragons dive down to one of the many rooftop collection sites we’ve installed across cities everywhere. Their thrill is in the adrenaline I suppose, and in beating each other with the precision of their fire breath. When they “win” with one hundred percent recapture of their flames, the animals seem to get boastful, backflipping and flying in circles around the younger, less accurate dragons.

That’s it. That’s all it really takes to make them happy. They repeat this process several times a day, for upwards of twelve hours a day, shifting their flight patterns to correspond with the sun’s adjustments, rather than the earth’s rotation. I never would have imagined such a simple solution to keep them on task.

There are hundreds of thousands of our dragons now across the world. Most we’ve charged for, and a few we’ve gifted as foreign aid to the poorest nations. We’re undeniably the premier energy capture system across the planet, and all because dragons really like to play.

••••

If you are one to stare up at the skies, if you look closely and wait patiently enough, you will see them. Teal is the only one of her kind, most of the dragons are red- or yellow-bottomed to better stand out against the sky that still occasionally holds hints of blue. They circle far above, glints of light acting as our daytime stars—a marvel, since we can no longer see true stars at night.

We haven’t saved everyone. The global population has shrunk since my company began its work. Many have been lost to horrific deaths of starvation over the years. But we are still here as a species. This fact will have to comfort me in the coming years, while I adjust to crossword puzzles, knitting, and whatever else I’m supposed to get down to in old age.

I stay on the roof a while, watching Teal get tinier and tinier until she’s indistinguishable from the steel-colored soup. Her flashier, red brethren dot the heavens, moving in lazy figure eights high above.

I wonder what it feels like as they sense the sun on their backs, and, for a minute, I’m overtaken with jealousy. Yes, we have cameras that give us some sense of what the beasts see; we can take virtual rides with them whenever we (or the interns) get curious. But I’ll never experience that vibrancy first-hand, the sensation that our ancestors wrote about in books and described in recorded interviews, the feeling of being permeated by those golden rays.

My knees creak, and I grasp more firmly to the cane I carry with me most days. It’s modeled after Teal, jet black, with a streak of her color spiraling around from base to the curved handle up top. If I had grandchildren, they would probably roll their eyes at my corny tribute.

It amazes me the way the body deteriorates, moves slower each day than the last. Just when I think I’ve figured it out, my joints reach a new level of concern. I’m gradually learning to let them be—I’m learning to let all manner of things be these days.

I turn toward the elevator. As I make my way, I feel a soft breeze float down to me and hear a gentle whoosh of air. A shadow crosses my path, and I smile without looking up.

Maybe I’m not the only one who is sentimental today. The outline of my lifelong charge hovers in place, strong and solid. I tap my cane delicately to the patch of concrete that holds the dark imprint of her form. And in so doing, I find myself giving in to the sudden urge to laugh.

It’s a big belly mover, a laughter of abandon, a hilarity I haven’t found for ages, maybe since I was a girl. I clutch my stomach in the throes of it and give in to the release. A cleanse.

Under her shadow, I think perhaps this is what Teal wanted from me all those years. Someone who understood that a game is a tool to carry us through to the next moment.

Stefani Cox

Stefani Cox is a Los Angeles-based speculative fiction writer, as well as an associate editor for PodCastle fantasy fiction podcast. She is an alumna of the VONA/Voices workshops, and her short fiction appears in FIYAH magazine, and the Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers anthology. You can find her on Twitter @stefanicox or on her website stefanicox.com.