Save Yourself: John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness and the Cinema of the Weird

by Victor H. Rodriguez

Issue 8: Weird | 1,715 words

© Nick Julia/Adobe Stock

“Anxiety is the aspect of our fear that looks to the future, anticipating potential problems and dangers.” – Jessica Care Moore

John Carpenter’s horror movie Prince of Darkness opened in 1987 to mixed reviews, barely breaking even its opening weekend. The plot involves a research team’s discovery of a mysterious cylinder in a deserted church located in a major city consumed by urban decay. The researchers are an ensemble of experts, each gifted in a specialized area of study. Upon further exploration of the site, all does not go smoothly. Unexplained events happen with mounting frequency; animals and humans display unfathomable patterns of behavior. The researchers experience strange “dreams.” The sealed cylinder’s formless contents are undoubtedly dangerous, and it appears to be opening itself…

Prince of Darkness is one of the best cinematic examples of the Weird, a term—popularized by 20th-century fiction writer H.P. Lovecraft—which doesn’t refer to a sub-genre as much as a sustained eerie mood across a narrative. Like the purposeful, protean contents of the cylinder, Carpenter’s movie has achieved a slow-burning success over the years, gathering strength on home video and by word-of-mouth. Thirty years later, Prince of Darkness has been recognized by filmmakers, critics, and fans to be a masterpiece.

To correlate the film’s contents to the Weird, we should take a brief look at the evolution of genre fiction. In the old days, little was known about the dangers lurking beyond our perceptions of the real world. We invented stories—and possibly the concept of storytelling itself—to give our fears a form, thereby making them less intimidating. Southern Utah University professor Kyle Bishop (guest host on the consistently excellent Horror Movie Podcast) explains, “Horror narratives allow us to cope with the anxieties that bother us the most in a safe, artificial environment.” By the Industrial Age, general knowledge of the dangerous became common enough that genre entertainment mutated it to include my favorite kind of antagonist: the formless threat.

Freud would categorize the formless threat in fiction as an uncanny reminder of our own id (repressed impulses). French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan took Freud’s studies further, linking this type of antagonist to a reminder of an unconscious narcissistic angst-causing impasse. Guys—sometimes a formless threat is just a formless threat.

In Prince of Darkness, one of the scientists, Brian Marsh, identifies that in the cylinder “a life form is growing out of pre-biotic fluids. It’s not winding down into disorder, it’s self-organizing. It’s becoming something. What? An animal? A disease? What?”

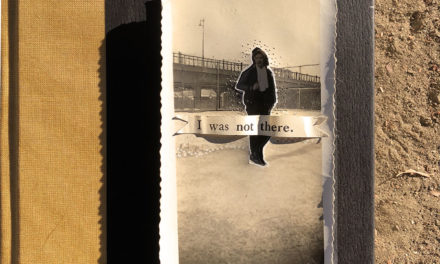

Protagonists in Weird narratives come face-to-face with an uncaring—often hostile—cosmos. Science brings dangerous knowledge, and faith is ineffectual. To heighten the unnerving atmosphere, the setting is crafted with realistic detail, yet the protagonist is often presented as unreliable. Even the condition of insanity can be subjective, less an affliction than a destination where anyone under certain circumstances can go.

••••

Genre fiction and movies often reflect the current fears of the public, and the Weird captures these anxieties in its narratives, as seen in the stories of both Carpenter and Lovecraft. Lovecraft’s highly imaginative sci-fi and horror stories anticipated mid-century worries surrounding deep sea and space exploration and present-day concerns of information overload. The introverted Lovecraft wrote what he knew, emotionally and intellectually. He was raised with inconsistent parenting—his paranoid mother suffered from mental illness and was in the habit of shifting her demeanor from overprotectiveness to hostility in a heartbeat. Born into dwindling privilege, he also suffered from xenophobia, ever fearful of the rising presence of the sociological Other, i.e., foreign faces, customs, and cultures.

John Carpenter read Lovecraft growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s. By then, the Weird had touched the mainstream. In the early 1950s, exploration to gather new information about the universe in which we lived was pushed to the technological limit, and the United States was caught up in the second Red Scare. Popular horror films depicting Western anxieties were invasion pictures like The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). By the 1960s, the United States was embroiled in the battle for unprecedented human rights advances. Combine a heightened awareness of societal change with the techniques and concepts employed by Lovecraft in his fiction, then add a rarely-equaled talent for filmmaking, and you get Carpenter’s work.

Carpenter Frankensteined parts of those mid-century sci-fi movies with connective tissue borrowed from several key Lovecraft stories to build the insidious antagonist of Prince of Darkness. The researchers in the film fall to the formless threat’s mental domination one by one. No one is sure who of their friends has been turned; controlled victims wander, zombie-like, among the sleep-deprived researchers, affirming their new allegiance by issuing dreadful warnings that undermine the morale of the unafflicted team members. This theme runs in other Carpenter films, like his 1982 The Thing.

YOU WILL NOT BE SAVED BY THE HOLY GHOST NOR THE GOD PLUTONIUM

Prince of Darkness, in keeping with the Weird, allows neither faith nor science to bring revelation or solution. Donald Pleasence, who plays Father Loomis (oddly the same last name of a character in another Carpenter film, Halloween), believes it may be humanity’s growing belief in science itself that empowers their foe. He laments, “It’s your disbelief that powers him. It allows his deception. He lives in the smallest parts of it.” This position changes later in the film when he exclaims, “Where are you…? Christ?”

The young scientists in Prince of Darkness, whom Carpenter cleverly makes the easiest characters the audience can identify with, are similarly cut no breaks. A few of my friends were physics grad students in the 1990s, young men and women who often scoffed at my love of horror narratives; they were surprisingly chilled by this one. Professor Birack, played by the late, great Victor Wong, expounds on how science is ultimately another system of faith and, consequently, only a partial answer:

“Let’s talk about our beliefs, and what we can learn about them. We believe nature is solid, and time a constant. Matter has substance and time a direction. There is truth in flesh and the solid ground. The wind may be invisible, but it’s real… None of this is true! Say goodbye to classical reality, because our logic collapses on the subatomic level into ghosts and shadows.”

OK, sure, I’ll take your word for it. I was a graphic design major! Still—even I knew this was an unsettling overture preparing us for an encounter with something that would confound our expectations.

Not all weird fiction questions science in the same way. In Lovecraft’s most famous story, The Call of Cthulhu, science is presented as a Pandora’s box: “Some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

IN FACT, YOU WILL NOT BE SAVED!

Weird stories provoke with an undefinable threat and ultimately end with no clean closure. In Prince of Darkness, the survivors—religious and scientific— begin working together and come up with an innovative, yet disturbing, solution. Though they push the immediate threat back, the characters are left haunted by the experience, illustrated in one of the most unsettling movie endings of all time. Lovecraft would have approved.

YOU HAVE TO SAFE YOURSELF

The Weird is more popular now than ever. Lovecraft’s stories have been adapted—sans horrendously racist content—to movies and television with astonishing frequency over the last fifty years. Interpolations and derivations of his work, a practice Lovecraft encouraged while he lived, are even more numerous (e.g., Jordan Peele named the enigmatic white patriarch in his Academy Award-winning script for Get Out after one of Lovecraft’s most famous characters—Dr. Armitage). The Weird resonates with anxieties surrounding our rapidly changing realities.

And while weird stories and Prince of Darkness don’t immediately present clear answers, we can still use them to navigate our anxieties of the unknown. One message in Prince of Darkness is clear: Everyone must save themselves; there’s no cavalry en route. Change is coming for all of us, and it will be uncomfortable. Even though humanity has a heroic, selfless side, we are ever balanced by selfishness, eternal conflict with one another, and conflict within ourselves.

There is only one solution, and—big surprise—it involves common sense. Even though each person is responsible for their own salvation, like Marsh and Loomis in the movie, we have to learn to work together.

There is no happy ending in Prince of Darkness, and there shouldn’t be. It’s not about happiness, it’s about doing the right thing. The Weird doesn’t offer an easy way out—quite the opposite—confronting the unknown is often harder than we first anticipate.

Irrevocable, life-altering change comes for us all. Once your children start fending for themselves in the world, deep down you know they will one day replace you. Survive a deadly disease, and you reevaluate your life’s priorities. We all know the Earth’s overpopulation is depleting it of the resources we need to live faster than we can replace them. However, change doesn’t always have to mean destruction. It could simply be starting a new phase of life, experiencing puberty, entering into a marriage, or starting a new career.

Whatever the change may be, it’s out of our hands and coming for us like an invisible monster, whether we’re ready or not. Do yourself a favor: prepare. Check out Prince of Darkness. I’d also recommend movies like Alex Garland’s excellent Annihilation (2018), and the literary fiction of Laird Barron, Junji Ito, or Victor LaValle—purveyors of what is now being called the New Weird. Meditate on the messages therein—they’re gold. A controlled confrontation with our anxieties is a healthy, positive thing. After all, what is anxiety except a side effect of protecting what we think is important from being lost. It follows, then, that we haven’t yet lost it! In any case, only those of us courageous enough to steer into the fear (explained in detail in the excellent self-help book The Tools by Phil Stutz and Barry Michels), will have the—ahem—tools to make the world a better place.

Victor H. Rodriguez

Victor H. Rodriguez is a talent manager and writer working out of the Strange, High House in the Mist in Seattle. He’s been a music supervisor, audio director, and soundtrack producer for film, television, and video games, including Hellbound: Hellraiser II, Crime Story, and Grand Theft Auto: Vice City. You can pick up a copy of his debut book THE SOUND OF FEAR—a collection of short horror stories—at Amazon now. Follow him on Twitter @dimestorecaesar, and visit his website at vhrodriguez.wordpress.com.